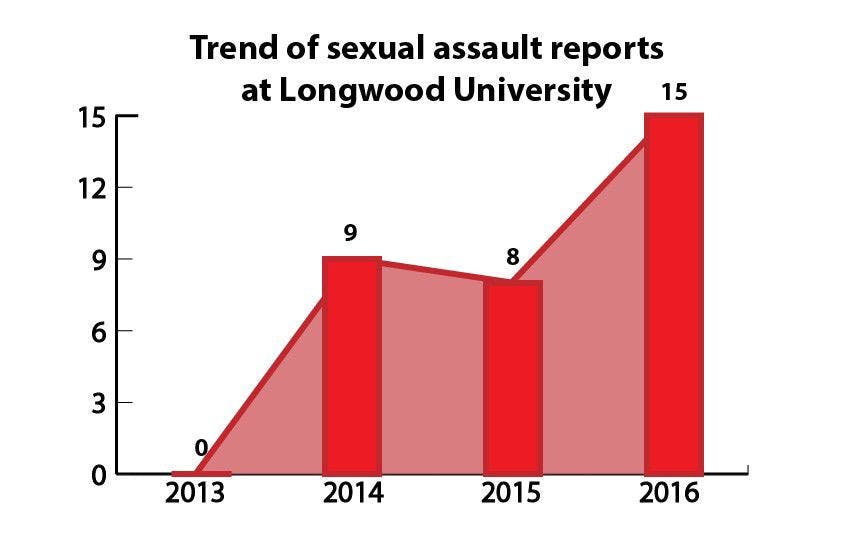

Within the past month, the Longwood University Police Department has received five reports of sexual assault. In 2016, the department has accrued a total of 15 sexual violence reports - sexual battery, sexual assault, rape - on Longwood-owned property.

The current number of reports has already surpassed 2015 by seven and 2014 by six. Three years ago, zero forcible- or nonforcible-sex offenses were reported, according to Longwood’s Jeanne Clery Act-mandated annual safety and security report.

In the past three years, the university’s police department has received a growing amount of sexual assault reports since the revisions of Longwood’s sexual misconduct policy in 2014.

“Statistically on a national level, we know that sexual misconduct, not just rape, but sexual misconduct in general is vastly underreported. I can tell you that over the past few years since we had our new policies, we’ve seen reports increase,” said Associate Dean of Student Conduct and Integrity Jenn Fraley, the university’s former Title IX coordinator. “I can’t tell you I know we’re in line with the national statistics, but that is my assumption.”

The timeline and length of campus sexual assault investigations varies with each report. While the most recent report of sexual assault on Sunday, Oct. 30 was closed and referred to Title IX within a few days, the report made on Sunday, Oct. 16 remains an ongoing investigation.

It isn’t known how many cases of sexual assault have occurred on property not owned by Longwood, falling under the Farmville Police Department’s jurisdiction, as the statistic isn’t kept by the department.

Farmville Deputy Police Chief Captain Bill Hogan said, “I could look up how many sexual assaults we’ve had, but it’s not going to tell me whether the victim was a Longwood student or not. I would have to go back and look at every one of those cases individually to pull it out.”

For the past decade, a national spotlight heated up the issue of sexual violence on college campuses as studies began to show its unspoken prevalence.

According to a 2014 Bureau of Justice national study, 37,846 students - 83 percent were female - experience completed or attempted rape or sexual assault, but 80 percent of cases went unreported to police from 1995-2013.

In a university environment, there are two separate processes for victims to report and pursue action after an incident - criminal and Title IX.

Longwood Police Chief Robert Beach and Fraley agreed while the proceedings and investigations typically occur simultaneously, the timeline and requirements of proof significantly differ.

“They’re two rails on a railroad track if you will, all headed toward the same conclusion, trying to make a safe campus and help a victim, but we don’t tie the two together,” said Beach.

Fraley added, “We’re not looking at the same process. It’s a very different standard, a very different procedure, even our definitions of consent are different.”

The Code of Virginia outlines the procedures and definitions involved in a criminal sexual assault case while Longwood University’s sexual misconduct policy guides the Title IX procedure, detailing definitions of consent, forms of sexual misconduct and the hearing process. Longwood’s sexual misconduct policy has been updated twice since August 2014 when it was revamped in response to national attention on campus sexual assault brought by The Rolling Stone’s now-debunked magazine article, “A Rape on Campus,” on an alleged gang rape at the University of Virginia.

The Rotunda spoke with an alleged victim, a Longwood student who agreed to speak on condition of anonymity due to the sensitivity of her experience, regarding her perspective seeking action through both the criminal and Title IX process in a phone interview.

“When something like that happens, you don’t want to keep remembering it, and you have to go into court multiple times and tell what happened to you multiple times over and over and over again ... It’s just like there’s no way to move on from it,” she said.

The alleged victim said she reported she was sexually assaulted by an intoxicated male Longwood student to Longwood housing officials the next day. In her situation, the court proceedings took nearly a year and resulted in finding the former suspect not guilty of an alleged sexual offense. The Title IX proceedings lasted over three months – beginning in November, interrupted by winter break, then ending in February – and found the same student responsible and placed him on disciplinary probation.

While Beach and Fraley said they receive reports from individuals, both agreed most come from third-parties, particularly resident assistants. After the initial reports, the investigations and process can diverge.

As university students are protected under the Family Education and Privacy Rights Act, the status and results of all Title IX proceedings aren’t available to the public, unlike criminal proceedings which are public record.

For criminal proceedings, Beach said the length of each investigation largely varies depending on “the complexities” unique to each situation. He said factors can include the amount of physical evidence available, length of time the victim took to report the case and the availability of a suspect.

According to Hogan, a “normal” sexual violence case will take at least a year to investigate and hear in court depending on if the victim is willing to participate.

“A lot of times in any sexual assault case, it’s often the victim's word against the suspect. It's one person’s credibility over another person’s credibility,” said Hogan. “Lacking any physical evidence in these cases, it’s extremely important for the victim to be completely honest and transparent even when things are embarrassing.”

Criminal cases begin with a report, then investigation occurs. Then, the file is sent to the commonwealth's attorney to determine if the case proves guilt beyond reasonable doubt and afterword, pre-trial hearings begin followed by the trial and the potential for appeals. Hogan described beyond reasonable doubt as over 90 percent certainty of a guilt.

To collect physical evidence, lab results from a Physical Evidence Recovery Kit (PERK), or rape kit, are usually vital to the officer’s investigation and take about six months to process and return to the agency, according to Hogan.

Beach said the time it takes for the commonwealth's attorney office to review the file and investigative report also changes with each case.

“We had one case last year where the commonwealth's attorney took several weeks to examine,” he said. “It’s going to be different in every case; some may be turned around in 24 hours, some may be days.”

The timeline described by Beach and Hogan were consistent with the alleged victim’s experience. Though she said her case didn’t involve physical evidence like a PERK results, solely camera footage of the incident and testimonies. The trial in general district court was set within three months of the preliminary hearing; the former suspect’s appeal extended the process.

At the general district court level, the judge found the former defendant guilty. In October, nearly a year after the initial incident, a jury at the circuit court level acquitted the former defendant, according to the Virginia Courts Case Information database.

Her case fell under Longwood police’s jurisdiction as it occurred on Longwood-managed property. She complimented how Longwood police handled her criminal case as well as they placed a second no contact order on the former suspect after the university did as well.

A no contact order in Virginia is a legally authorized protective order prohibiting direct or indirect contact, according to the Virginia Court System.

“The Longwood Police, they did their job. They were proactive in coming to me and getting a statement and making sure I was comfortable and making sure I felt safe,” said the alleged victim. “The Longwood police are very supportive, at least for me, of the sexual assault. Obviously, they can’t always prevent it from happening, but I feel like in the aftermath of that they really do a wonderful job.”

In Title IX proceedings, the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights requires universities to complete their process in 60 days, unless they reasonably justify a delay.

“The administrative side of things in terms of Title IX moves much quicker than a criminal investigation, just because it is such a different process,” said Fraley. “We are not talking about a criminal burden of proof. Our standard of proof across the board for Title IX as well as all student conduct issues is a preponderance of evidence which is that 51 percent.”

While Fraley said their process can vary from the 60-day timeline, she said it contrasted with the length of criminal proceedings due to Title IX’s lower standard of proof and dependence on interviews with involved parties versus waiting for physical evidence like PERKs.

In the Title IX process, individuals who report incidents are called complainants while the accused party is called the respondent, according to Longwood’s sexual misconduct policy.

In the alleged victim’s case, she said her Title IX case was ongoing for over three months following the initial incident after the respondent filed an appeal on the result of the initial hearing then called on the morning of the hearing to say he couldn’t appear on the date set for the appeal hearing, delaying the final decision until after the winter break in February.

“It was originally supposed to be within two months, but it wasn’t,” said the alleged victim, who didn’t feel it was a justifiable reason to delay the hearing. “I was depressed and had really bad anxiety, and I still showed up to the Title IX cases and both court cases. I didn’t even get out of bed to go to class, but I still went to those cases because I made it a priority.”

Within Longwood’s sexual misconduct policy, it states proceedings will take 60 days “barring extenuating circumstances,” but doesn’t provide specific examples.

Fraley said some reasons may range from a need to conduct an unusually large number of interviews during the investigation process to being required to provide adequate notice between hearings.

Typically, Fraley and Beach said information flows fluidly between the police to Title IX investigators. Fraley said the investigation phase usually takes the longest and varies the most in a standard Title IX procedure.

Both Fraley and Beach noted participation in investigations on either side is voluntary.

“People don’t have to talk to the police, that is their constitutional right,” said Beach.

The alleged victim said both the Longwood police and Title IX investigator were thorough as they collected information and evidence in her case. She said the respondent didn’t give a statement in the Title IX investigation.

In Title IX proceedings, the final hearing leads to finding a respondent responsible or not responsible for the incident. If found responsible, the University Hearing Board will issue a sanction, according to Fraley.

Longwood’s sexual misconduct policy lists six potential actions - a requirement not to repeat or continue the conduct, reprimand, reassignment, suspension, termination of employment, expulsion, but adds that the hearing board is “not limited to” issuing those six.

The hearing board is made of five members and are renewed annually, selected by Longwood’s faculty senate executive committee, the vice president for student affairs and vice president for finance and administration, according to Longwood’s sexual misconduct policy.

In the alleged victim’s circumstance, she said the respondent was found responsible for the offense of sexual battery in both the initial and appellate hearings, but felt he was given the minimum sanctions “to cover their asses.” She said he was placed on disciplinary probation and prohibited from living in the same building as her, but was disappointed the board allowed him to remain on campus.

“It was like I just couldn’t get away from the cases, the court cases, the Title IX cases, but also him, because I kept running into him on campus over and over and over again,” said the alleged victim.

After her cases ended, she said she left Longwood on medical leave after facing anxiety and panic attacks for a year. She returned to Longwood for classes this fall, but remained a commuter student due to her safety concerns.

The sexual misconduct policy doesn’t provide guidelines for what is required to receive each sanction, stating it “depends on the facts and circumstances of the offense and/or any history of past conduct that violates this policy.”

“Because our policy covers so much in terms of sexual misconduct, anything from sexual harassment all the way through sexual assault,” said Fraley, “because there’s such a big spread there in terms of behaviors, it’s hard to pigeonhole what something is going to fall in terms of a recommended sanction.”

Both the alleged victim and her mother suggested Longwood provide resident assistants with additional training to improve their ability to recognize sexual assault, analyze the situation and support allegations.

The Rotunda reached out to Fraley for university comment regarding the suggestions offered by the alleged victim and her mother, but was unable to receive comment in time for print. A follow-up will be printed including her response.

To grow from her experience with the result of Longwood’s Title IX process, the alleged victim said her largest takeaway was the responsible party remaining on campus.

“He just seemed like he was everywhere, and it just made it really hard not only recover, but to move on from it after it was over because every time I saw him it brought everything back,” she said. “I had to put my life on hold.”